Chapter 7

media

- extracted text

-

The Siege of Fort Erie

54

The Sortie

few determined officers spurred among the malcontents, arrested

the ringleader, awed his followers, and, aided by a small detachment of regulars, restored order." The refractory jurist was

hustled into a wagon and sent under arrest to Williamsville with

the information that if he ever returned to Buffalo he would be

shot without benefit of clergy.

The force then moved off without further trouble, crossed

the river, and camped on the lake shore to the left of Towson's

battery, throwing up a sod breastwork for protection. This

occurred on September tenth. Their arrival was not hailed with

great enthusiasm by the regular army contingent of the garrison, whose confidence in militia seems to have been somewhat

shaken. But these same troops, ununiformed, and poorly drilled

and equipped, soon showed that if they could not drill they could

fight; and by their gallant conduct they did more than their share

toward redeeming the reputation of the American militiaman

during this war.

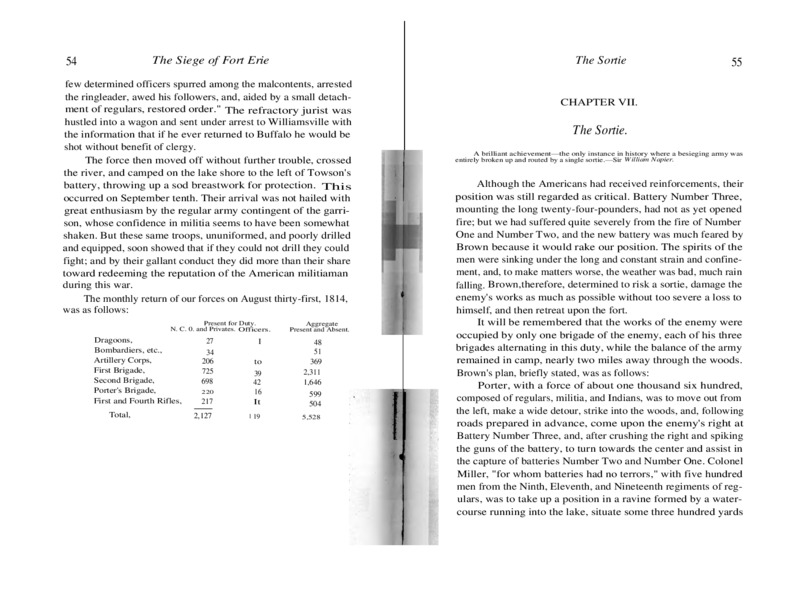

The monthly return of our forces on August thirty-first, 1814,

was as follows:

Present for Duty.

N. C. 0. and Privates. Officers.

Dragoons,

Bombardiers, etc.,

Artillery Corps,

First Brigade,

Second Brigade,

Porter's Brigade,

First and Fourth Rifles,

Total,

27

34

206

725

698

I

Aggregate

Present and Absent.

217

to

39

42

16

It

48

51

369

2,311

1,646

599

504

2,127

1 19

5,528

220

55

CHAPTER VII.

The Sortie.

A brilliant achievement—the only instance in history where a besieging army was

entirely broken up and routed by a single sortie.—Sir William Napier.

Although the Americans had received reinforcements, their

position was still regarded as critical. Battery Number Three,

mounting the long twenty-four-pounders, had not as yet opened

fire; but we had suffered quite severely from the fire of Number

One and Number Two, and the new battery was much feared by

Brown because it would rake our position. The spirits of the

men were sinking under the long and constant strain and confinement, and, to make matters worse, the weather was bad, much rain

falling. Brown,therefore, determined to risk a sortie, damage the

enemy's works as much as possible without too severe a loss to

himself, and then retreat upon the fort.

It will be remembered that the works of the enemy were

occupied by only one brigade of the enemy, each of his three

brigades alternating in this duty, while the balance of the army

remained in camp, nearly two miles away through the woods.

Brown's plan, briefly stated, was as follows:

Porter, with a force of about one thousand six hundred,

composed of regulars, militia, and Indians, was to move out from

the left, make a wide detour, strike into the woods, and, following

roads prepared in advance, come upon the enemy's right at

Battery Number Three, and, after crushing the right and spiking

the guns of the battery, to turn towards the center and assist in

the capture of batteries Number Two and Number One. Colonel

Miller, "for whom batteries had no terrors," with five hundred

men from the Ninth, Eleventh, and Nineteenth regiments of regulars, was to take up a position in a ravine formed by a watercourse running into the lake, situate some three hundred yards

The Siege of Fort Erie

The Sortie

southerly from the enemy's line, and, when the noise of Porter's

attack was heard, to rush in between batteries Number Two and

Number Three, and attack Battery Number Two and then Number One. General Ripley,who, it is claimed, had no confidence in

the success of the enterprise, and, as Brown states, wished to take

no part in it, was stationed with the Twenty-first Regiment as a

reserve out of sight between the westerly bastions of the fort.

Major Jessup, recently wounded, was left to garrison the fort with

the Twenty-fifth Regiment, only one hundred and fifty strong.

The plan of attack was simple, and, if success is any criterion,

extremely effective.

On September sixteenth Lieutenants Frazer and Riddle, with

one hundred men each, fifty armed with muskets and fifty with

axes, labored all day without being discovered, constructing rough

roads for Porter's columns up to within one hundred and fifty

yards of the British position. They also built underbrush roads

back to the fort from a point near the front of the British position

in order that the retreat might be unobstructed and the miry and

i mpassable places avoided. Much rain had fallen during the past

twelve days, and the ground in front of our position was little

better than a swamp.

The morning of the seventeenth dawned cloudy and disagreeable, and a light rain was falling. During the forenoon the

volunteers were paraded, and, after arousing their enthusiasm by

the announcement of the recent American victories at Plattsburg

and Lake Champlain, the plan of the proposed sortie was revealed

to them. It was enthusiastically received. Each volunteer was

thereupon directed to take off his headgear and tie a red handkerchief or red cloth around his head so that he might be readily

distinguished, none of them being uniformed. As the day wore

on the rain increased, and a hard thunderstorm, almost a gale,

came up, which continued during the attack. This undoubtedly

aided our forces in advancing unperceived to the attack until

right onto the enemy's works, but many of our muskets were

disabled through water getting into the pans of the guns.

In the afternoon Porter moved out to take up his position on

the enemy's right. He sent forward as an advance two hundred

riflemen, with some Indians, under Colonel Gibson. The balance

of his force was divided into two columns, which marched parallel

to each other, following the brush roads. They were guided

respectively by Riddle and Frazer. Lieutenant Colonel Wood

commanded the right column, which was composed of four

hundred regulars and five hundred militia. These troops were

to attack the enemy's position. Brigadier General Davis, of

Batavia, who, while senior to Porter, volunteered to muster his

brigade and fight under him, waiving all question of rank, commanded the left column consisting of five hundred militia newly

raised. This column was intended to engage the enemy's reinforcements if any should be thrown in.

These columns reached their position a few yards from the

right of the enemy's position without discovery, and at about

three in the afternoon Brown gave Porter the order to attack.

This order was executed with great vigor, and the cheers of the

Americans as they rushed to the assault were plainly heard by

the anxious listeners upon the American shore, notwithstanding

the storm that raged.

The British lines that day were guarded by the Second

Brigade, consisting of the Eighth and De Watteville's regiments of

regulars. The swiftness of the attack utterly surprised these

troops, and the Americans soon captured a blockhouse in the

rear of Battery Number Three, and then the battery itself, destroying the much dreaded twenty-four-pounders and their carriages

and blowing up a magazine. Here the brave Wood* and Brigadier General Davis fell mortally wounded. The loss of both of

these men was greatly mourned.

Porter then swung his forces around and attacked Battery

Number Two conjointly with Major Miller, who had rushed forward as soon as Porter's attack was heard. After a sharp struggle

56

57

* In the cemetery at West Point, a short distance from the grave of General Scott, stands

a cenotaph erected by General Brown to the memory of Lieutenant Colonel Wood. It was

dedicated in 1858, and the inscription states that he fell while leading a charge at the sortie of

Fort Erie, September seventeenth, 5854, in the thirty-first year of his age.

4

58

The Siege of Fort Erie

this battery was captured. Battery Number One was, so Brown

says, abandoned by the enemy. At all events, it was captured;

but by reason of the confusion, and the stout defense the British

soon made, the Americans neglected or were unable to permanently injure batteries Number One and Number Two, although

they were temporarily disabled.

Owing to the suddenness and impetuosity of the American

attack, the Second Brigade of the enemy was crumpled up and

driven away before any arrangements could be made to meet the

attack. It is a maxim of war that "when a force is not deployed

but is struck suddenly and violently on its flank, resistance is

i mpracticable." Chancellorsville, where the Eleventh Corps of

the Union army melted away before Jackson's fierce onslaught,

was an illustration of the truth of this maxim. This attack was

another; and our troops soon swept the front line of intrenchments almost clear of the enemy.

So far the Americans had accomplished much with little

loss, but the end was not yet. As soon as the American attack

was heard, De Watteville promptly sent back to the British camp

for reinforcements, and the First and Third brigades hastened to

the succor of the Second Brigade. In the meantime the Second

Brigade was rapidly recovering from the demoralization from

which it had at first suffered.

The British lines were defended by felled trees, entanglements, and abattis, and whilst the Americans were struggling to

penetrate these defenses they were met with a hot fire from the

enemy posted in the traverses and along the parallel lines of

intrenchments. Then too, at this stage of the attack the enemy's

reinforcements arrived and commenced a determined resistance

to the further advance of the Americans. The fight now raged

furiously. Hand-to-hand encounters occurred all along the line,

and sometimes with the bayonet and sometimes with rifle fire the

enemy sought to regain possession of the lines and drive off the

Americans, now somewhat confused by the constant fire concentrated upon them from all points and through penetrating the

The Sortie

59

abattis and entanglements. Although outnumbered, the Americans stubbornly resisted, and, regardless of the hot fire, gave

back blow for blow.

Brown, fearing for Miller's safety, ordered Ripley forward to

his assistance, who prompty advanced with the Twenty-first Infantry. Ripley soon received a serious wound in the neck, and

was borne to the rear.*

Miller, with excellent judgment, appreciating that nothing

further could be accomplished, and in view of the superior force

of the British, began an orderly retreat towards the fort ; and

Brown soon ordered the other columns to do the same, for the

object of the sortie had been accomplished. They all reached

the fort in good order, but with considerable loss, for by this time

the British were pressing them fiercely. Thus in barely two hours

the result attempted had been achieved, the enemy irreparably

crippled, and one thousand men killed, injured, or taken prisoners.

General Drummond speaks of the retreat of the Americans as

a " precipitate retrograde movement made by the enemy from the

different points of our position of which he had gained a short possession." It should be observed, however, that Drummond, what, ever his faults were as a soldier, was a pronounced success at what

might be termed an explanatory writer. Some one has remarked

of Cellini that he created his own atmosphere. The same remark

applies to Drummond. His despatches to his government are

well worth a perusal. Ingersoll, in his history of the war, dryly

remarks apropos of this part of Drummond's report:

"The coincident exertions of both commanders, Brown to

withdraw his men from, and Drummond with his to recover, the

British entrenchments, soon effected it."

In this sortie we lost seventy-nine killed, two hundred and

sixteen wounded, and two hundred and sixteen missing, a total

of five hundred and eleven. Of this number twelve officers were

• Ripley never fully recovered from this wound, although he afterward served a term

in Congress.

The Siege of Fort Erie

The Sortie

killed, twenty-two wounded, and ten were missing—a most serious blow to the effectiveness of so small an army.

The enemy's loss in killed, wounded, and missing was somewhat under one thousand, and, according to the American accounts, we captured nearly four hundred prisoners. In any event,

the Americans totally disabled his best battery and injured the

others, besides destroying the morale of his troops. Only the pen

of a Drummond could convert this disaster into a repulse of the

Americans, which he did with ease. According to Drummond's

report his loss was one hundred and fifteen killed, one hundred

and forty-eight wounded, and three hundred and sixteen missing

—a total of five hundred and seventy-nine.

During the progress of the fight crowds lined the American

shore and listened to the combat during the lulls in the severe

storm which raged that afternoon. Dorsheimer thus dramatically

describes what was probably a very simple incident :

Holler, at one time secretary to Porter, in an article in volume six

of The Magazine of American History, says:

6o

"All through the afternoon no tidings came. Just at dusk

a small boat was seen struggling in the rapids. An eager crowd

soon gathered on the beach. In the midst of the breakers the

little bark upset. One of its crew was seen floating in the waves.

The bystanders made a line by holding on to each other's clothes,

and, stretching out from the shore, seized the drowning man. As,

exhausted and chilled, he staggered up the beach, he gasped into

the ears of his rescuers the first news they had of the great conflict and victory."

Many friends of General Porter have contended that the

sortie was planned by him and that he suggested it to Brown.

Brown makes no mention of this in his official report or in his

manuscript memoirs. Porter was a man of much more capacity

than Brown, and it is quite likely he had to do with planning the

attack, although Brown was by no means averse to any plan

which would insure fighting. In any event, Porter was selected

to lead the most important column, composed partly of regulars

not in his brigade, which is a significant fact in Porter's favor.

61

"Before battery No. 3 was completed, one bright morning

early in September, as General Porter, Lt.-Col. Wood, and Major

McRea of the engineers were walking from Towson's battery

towards the Fort and discussing the progress of the enemy's

offensive operations, Lt.-Col. Wood half-jestingly suggested that

it might be expedient to attempt a sortie. But no serious proposal of such an enterprise was made until some days later,

when General Porter invited his two friends to his quarters to

examine a plan for it which he had prepared. This plan was

discussed and fully matured in several confidential meetings of

the three officers. It was then submitted to General Brown, who

was still at Buffalo, whither he had retired, as has been stated,

after being wounded at the battle of Lundy's Lane. He neither

encouraged nor discouraged it at the outset, but, on examination

of it as thoroughly as possible in his absence from the ground, he

rather objected to the project.

"General Porter, however, continued to urge it, and his views

were warmly seconded by the two able engineers to whom he

had fully explained his plan. The whole army, General Brown

included, reposed the greatest confidence in these two officers,

particularly in Lt.-Col. Wood.

" General Brown finally required General Porter, whom he

considered responsible for the plan, to give him a written statement of its details over his own signature. After receiving this

document General Brown consented that the enterprise should be

undertaken, and directed General Porter to lead it."

On the other hand, Major Jessup, at that time serving in the

garrison, states positively that the sortie was planned solely by

Brown ; and he was certainly in a position to be well informed as

to what transpired in the little garrison. Major General Brown

was in command, and as he assumed the responsibility for the

movement he is entitled to the credit of its success.

The Sieg e of Fort Erie

The Sortie

An incident during the sortie, in which General Porter was

the hero, is worth repeating. General Porter, so the story runs,

while accompanied only by his orderly, was proceeding between

batteries Number One and Number Two, when, too late to retreat,

he suddenly came upon a small company of the enemy standing

at ease apparently waiting orders. Coming up as though at the

head of a regiment, Porter cried, "That's right, my good fellows,

surrender, and we'll take good care of you." The ruse succeeded,

and man by man the company from right to left threw down

their arms and marched to the rear. Everything went well until

the man next to the left guide was reached, who, not seeing any

soldiers supporting Porter, and suspecting the trick, came to

charge bayonet and demanded that Porter surrender. The boot

was now on the other leg, but Porter dextrously seized the musket and endeavored to wrest it away from the soldier. Several

comrades came to the man's assistance, and in the melee Porter

was thrown down and wounded in the hand. Struggling to his

feet, he told his assailants they were surrounded and if they

did not cease their resistance he would put them to death.

This created a slight diversion, and at this juncture Lieutenant

Chatfield, of the militia, at the head of the Cayuga Rifles, came

up, thus relieving Porter of an embarrassing situation and securing

the prisoners as well. This story smacks of the political campaign more than of the particular campaign with which this

narrative deals, but it may be true. In any event, Porter, in his

official report, mentions Chatfield as one "by whose intrepidity I

was, during the action, extricated from the most unpleasant situation."

On the twenty-first Drummond in great haste retired to the

old position of the British at Chippewa Creek, leaving some of

his stores at Fort Erie and destroying others at Frenchman's

Creek. The raising of the siege showed how severely Drummond

felt the sortie if his reports do not. It practically closed the

campaign upon the Niagara frontier, which since July third, 1814,

had waged with great fierceness.

The following table of losses is interesting, although it should

be remembered it does not include the losses in skirmishes and

minor combats, which were constantly taking place. It is taken

from General Wright's Life of Scott, and differs very slightly from

the figiffes already given.

-

63

Total

British

Loss.

Total

American

Loss.

507

Battle of Chippewa, July fifth, 1814,

Battle of Niagara (Lundy's Lane), July twenty-fifth, 1814, 878

Battle of Fort Erie, August fifteenth, 1814,

905

800

Sortie at Fort Erie, September seventeenth, 1814,

86o

84

3,090

1,783

Total,

328

511

When we consider that neither side had over four thousand,

if that number of men, engaged at any time, the immense percentage of loss will be appreciated.

General James Miller, writing two days after the sortie, says :

" I was ordered to advance and get into the enemy's works

before the column had beaten the enemy sufficiently to meet us

at the batteries. We had no alternative but to fall on them, beat

them, and take them. It was a sore job for us. My command

consisted of the 9th, 11th, and 19th Regiments. Colonel Aspinwall commanded the 9th and 19th and Colonel Bedel the 11th.

Colonel Aspinwall lost his left arm, Major Trimble of the 19th

was severely, I believe mortally, wounded through the body.

Captain Hale of the 11th killed; Captain Ingersoll of the 9th

Wounded in the head, and eight other officers severely wounded

some of them mortally. Colonel Bedel was the only officer

higher than a lieutenant in my whole command but what was

killed or wounded."

After Drummond left our front the fort was garrisoned with

a small force; and the volunteers, who were praised on all sides

for their steadiness and bravery during the whole campaign, and

especially the sortie, were dismissed to their homes. General

64

The Siege of Fort Erie

Brown put the matter in a few words when he said in a letter to

Governor Tompkins, "The militia of New York have redeemed

their character—they behaved gallantly."

The raising of the siege was completely decisive, and the

pioneers along the frontier could again rest in peace without the

disturbing thought that they might be scalped or burned out, or

both, before another day dawned. The fort was occupied until

November fifth, 1814, when it was blown up and destroyed and

the stores and garrison withdrawn to Buffalo, its possession being

no longer of value.

The War of 1812 has been overshadowed by the more important events which preceded and followed it, but when an

adequate history of this trying period of our country's history is

written, and the battles along the Niagara frontier are recounted,

Chippewa, Lundy's Lane, and Fort Erie will be awarded places

high up in the record of the many valorous deeds the history of

our country affords. And while the history of our brave men is

written, let due praise be accorded to our former foes, who, through

the mutation of time and circumstance, are now our nearest neigh.

bors and best friends.

THE END.